Philosophical Foundations of Sustainability

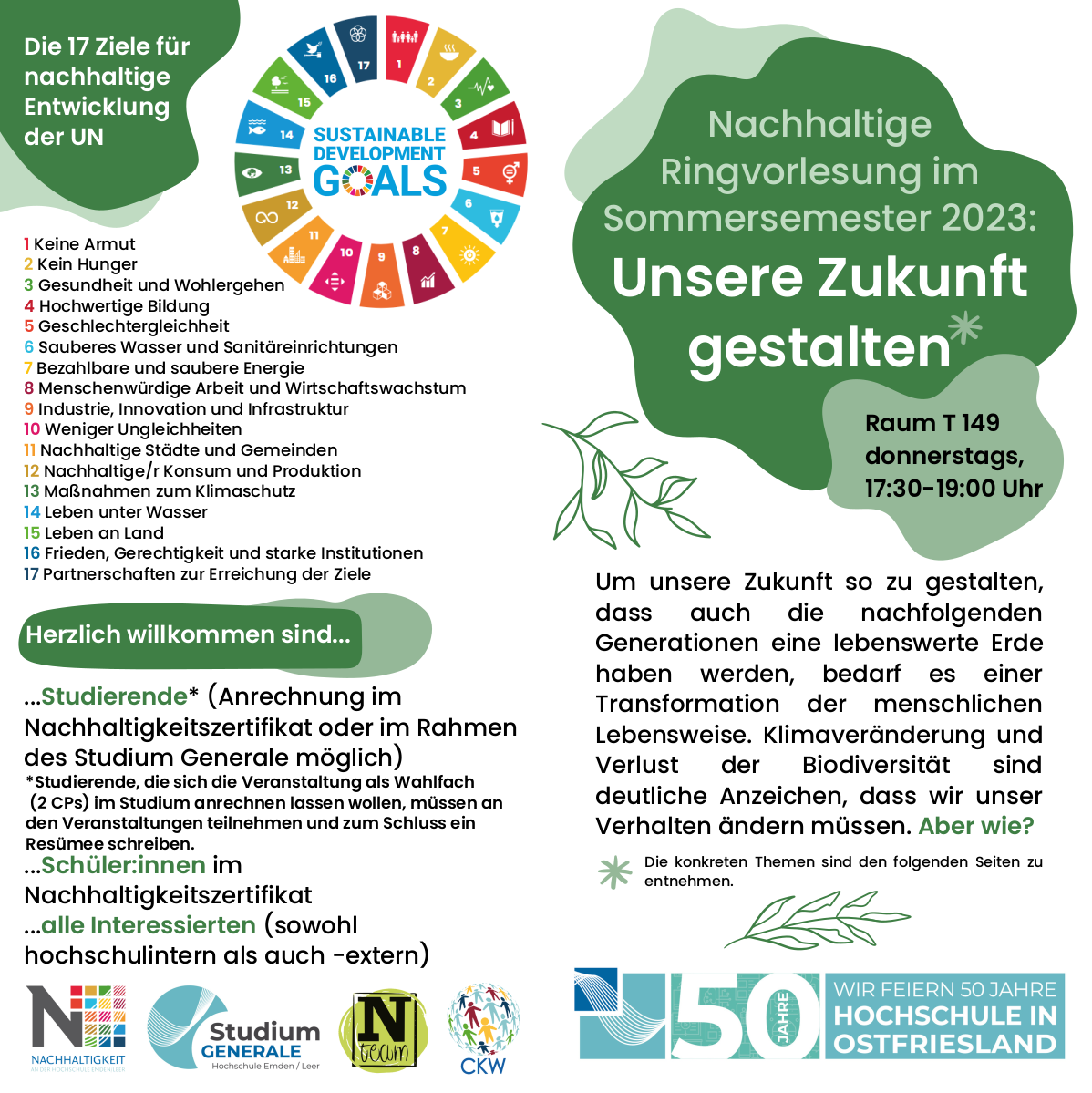

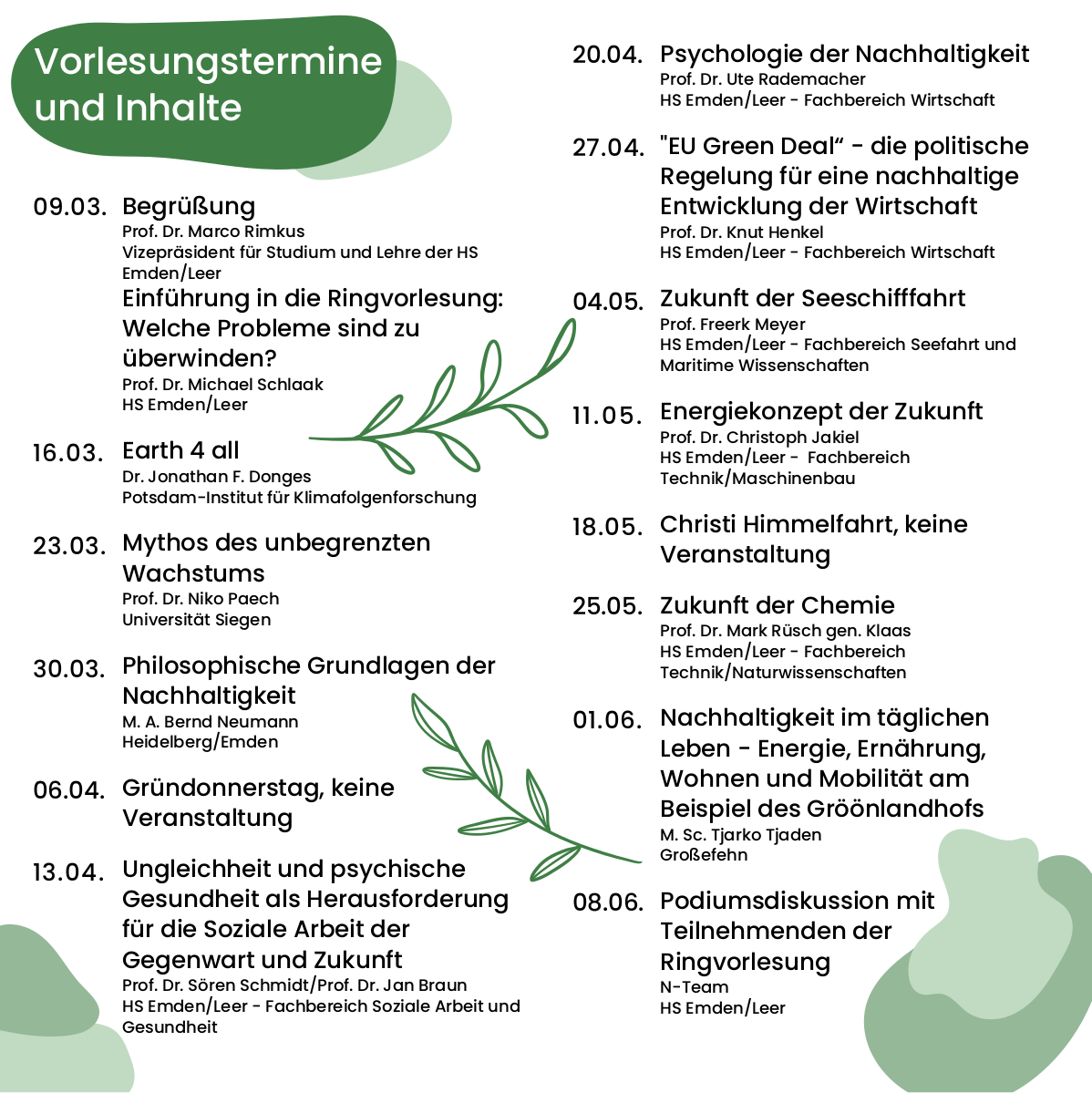

The University of Applied Sciences Emden/Leer is celebrating its 50th anniversary. As sustainability is always a major concern both in teaching and in the daily life at the university, one of the events the university is celebrating its anniversary is a special lecture series entitled unsere Zukunft gestalten

(shaping our future). Speakers from a wide range of disciplines present a broad view on problems of sustainability and possible solutions. On the 30th of March, I was allowed to contribute to this lecture under the title Philosophische Grundlagen der Nachhaltigkeit

(Philosophical Foundations of Sustainability).

In this lecture I ask two questions. The first is a moral philosophical one: Is there a duty to sustainability?

The primary issue here is the problem of justifying a moral duty to preserve the planet and the climate as the basis of life for future generations. The second question is of an economical-philosophical nature and is directed at the meaning of the term sustainability: What (and how much) should be sustained?

I will explain opposing positions on both questions. However, this is not done to contrast right and wrong, but to give an impression of the range of possible answers.

It starts with Derek Antony Parfit. He shows with the Non-Identity-Problem that a duty to sustainability principally cannot be justified, and with the No-Difference-Argument how to deal with this. I then present how a classic of sustainability philosophy attempts to justify this duty: We talk about Das Prinzip Verantwortung

(The Principle of Responsibility) by Hans Jonas. On the second question two economists have their say. The first is Robert Solow with the concept of weak sustainability

, which I contrast with Herman Daly's conception of strong sustainability

. At the end I will cite some hopefully inspiring words from John Stuart Mill on the Stationary State

, that is today known as post growth economy

.

Outline

1. Is there a duty for sustainability?

Derek Antony Parfit: Non-Identity-Problem

Derek Antony Parfit: No-Difference-Argument

Hans Jonas: The Principle Responsibility

2. What (and how much) should be sustained?

Robert Solow: Weak Sustainability

Herman Daly: Strong Sustainability

John Stuart Mill: Stationary State

Literature

1. Is there a duty for sustainability?

We can choose a sustainable economic lifestyle for different and good reasons, in order to preserve the basis of life for future generations. More and more people are already doing so because they don't like the idea of destroying the planet. Something else is the claim that it doesn't matter whether you like it or not, because everyone has a moral duty to preserve the basis of life for future generations. The claim is that it is not up to the individual's free choice to live sustainably or not, but that everyone has a duty to do so; just as one must not harm others of one's generation. And such a duty must be justified.

Derek Antony Parfit: Non-Identity-Problem

An essential difference between duties towards people of the present generation and those of future generations is that the latter do not (yet) exist. The non-identity problem of Derek Antony Parfit (1984: ch. 16.) focuses on this difference: According to this problem, we are today faced with the decision to either choose a sustainable lifestyle or to continue as before. This decision affects our way of life so fundamentally and comprehensively that human history will proceed differently. Part of this is that in both cases other couples will marry and other children will be born. The couple that meets during a short vacation with air travel will not meet like this in a sustainable economy, and they will accordingly not have children together. The point of the non-identity problem is that people living on a destroyed planet cannot complain because otherwise they would not have been born at all.

The non-identity problem arises because rights and duties can only be thought of with actual bearers of these rights and duties. To grant non-existing individuals even the most basic rights immediately leads to absurd duties for the existing ones: Suppose we were to grant non-existent individuals at least the right to life, the right to exist, all existing individuals would have the duty to have every child they could. This demand, of course, is absurd; but the fact that even a right to life for non-existent individuals leads to absurdities makes vivid that they cannot have rights. The non-identity problem can therefore also be formulated as a paradox: The individuals of a future generation, who have to live in a destroyed environment, would have a right to better living conditions only because we have violated this right.

Derek Antony Parfit: No-Difference-Argument

Derek Antony Parfit was convinced that a duty towards future generations is unjustifiable. But as troubling as the consequence of the non-identity problem may be, he surprisingly did not take it as an occasion to worry less about future generations. This view is what Parfit calls the No-Difference View:

We may be able to remember a time when we were concerned about effects on future generations, but had overlooked the Non-Identity Problem. We may have thought that a policy like Depletion would be against the interests of future people. When we saw that this was false, did we become less concerned about effects on future generations?

When I saw the problem, I did not become less concerned. And the same is true of many other people. I shall say that we accept the No-Difference View.

Parfit: Reasons and Persons. Chap. 16. Nr. 125.

The no-difference-argument addresses the fact that it is morally bad if someone is harmed independently of the concrete identity; or simply said: The identity of the person, which the non-identity-problem is referring to, does not matter at all in certain cases. For such a case, Parfit gives a medical ethics example: Suppose there were two diseases which newborn babies can be born with. In the case of the first, the woman must be tested before becoming pregnant, and if she is positive, the treatment is that she must not become pregnant for three months. The second disease can be diagnosed during pregnancy and treated with a simple medication.

Assume that everything else (severity of the disease, prevalence of cases, cost of diagnosis and treatment, etc.) is the same in both diseases except for the differences mentioned above. Now we are asked whether one of the two therapies is morally more valuable or more important. To this, most people respond that neither is in any way better or more valuable than the other. In terms of the non-identity problem, the difference is that in the first case a later conceived and thus different child is born, while in the second case the same child is born. Therefore, one would actually have to say that the second therapy is more valuable, because in the first case the child could not complain later about the lack of treatment, as otherwise it would not have been born. However, this difference with respect to identity apparently makes no difference at all with respect to moral value: Hence, it is called the no-difference

argument.

The decision for or against a sustainable economy for future generations is similar: According to the non-identity problem, the individuals of future generations cannot be bearers of rights which it would be our duty to respect. As with the child in the first case, we could reject the complaint of future generations about a destroyed planet by saying that otherwise they would not have been born at all. However, we do not do so; instead, we consider adverse living conditions for future generations to be morally bad, without making any distinction regarding the identity of the individuals. Thus, we accept the No-Difference View.

Hans Jonas: The principle Responsibility

Hans Jonas approaches the problem of justifying a duty to be sustainable quite differently from Parfit. In the 1979 classic of sustainability philosophy, The Principle of Responsibility

, Jonas presents an ethic for the technological civilization. Technological progress, according to Jonas, was long considered a pledge and promised the happiness of mankind. Today, however, we see that our advanced economy, and especially the waste it produces, has become an existential threat. This calls for a new kind of ethics, because our previous ethical thinking is not suitable to deal with the problems of technological civilization. Therefore, Jonas calls for and develops a future ethics

that addresses the long-term existence of humanity.

I would like to point out three aspects which such a future ethics must be able to answer, and which traditional ethics cannot answer: First, an ethics of the future must be able to deal in terms of space and time with much larger horizons. In traditional ethics, these horizons are comparatively short, because they concern the sphere of individual human actions. A future ethics, on the other hand, must be able to deal with environmental problems that will first become visible in decades or centuries, in the example of nuclear waste in millennia. And while, with regard to the spatial dimension, local effects are relevant for the objects of traditional ethics, global effects of actions are the rule in the case of future ethics.

Therefore, secondly, scientific knowledge plays a crucial role for future ethics due to the complexity of global ecological interrelationships. Traditional ethics requires little more than everyday knowledge: Stabbing someone in the body with a knife can fatally injure them, and the mail package in front of the neighbor's apartment is not there for everyone to take. Climate models, that tell us what consequences an unchecked emission of carbon dioxide will have, are something completely different. (cf. Jonas 1979: 66, 206f.).

The third difference between traditional ethics and future ethics is similar to Derek Antony Parfit's non-identity problem. Jonas argues that someone can only have rights if they can make (morally legitimate) claims; and only by this right reciprocally arises the duty for others to respect that right. But the nonexistent individuals of future generations do not and cannot make claims, so they can have no rights and we can have no duties towards them. Jonas writes:

Because only what makes claims has claims – that first of all is. All life makes claim to be alive, and perhaps this is a right to be respected. The non-existent makes no claims, therefore cannot be violated in its rights. […] Above all, it has no right to be at all before it in fact is. The claim to being begins only with being. But it is precisely with the not-yet-being that the ethics sought has to handle, and its principle of responsibility must be independent, as of all idea of law, so also of that of reciprocity.

Jonas: Das Prinzip Verantwortung. Seite 84.

(Own translation.)

The future ethics we are looking for must be able to deal with these three problems, which do not touch traditional ethics. For this purpose, Jonas formulates a categorical imperative (valid without further conditions) in analogy to Kant. This imperative has become known in the concise form: Thus the imperative is, that there be mankind […]

(Jonas 1979: 91. Own translation.). In other passages, Jonas expresses it in more detail:

An imperative would go something like this:

Jonas: Das Prinzip Verantwortung. Seite 36.Act in such a way that the effects of your action are compatible with the permanence of real human life on earth; or expressed in negative terms:Act in such a way that the effects of your action are not destructive to the future possibility of such life; or simply:Do not endanger the conditions for the infinite continuation of mankind on earth; or again expressed in positive terms:Include in your present choice the future integrity of man as co-object of your will.

(Own translation.)

By detaching the object of duty from the individual level and putting in its place the idea of humanity as a whole, Jonas succeeds in addressing a horizon that is both global in space and unlimited in time, as well as the complexity of the ecosystem that serves as the basis of life not for a particular person but for humanity as a whole. And since humanity exists as a whole, it can also be the subject of the duty that our individual and collective actions must not endanger its permanence.

Other concrete duties follow from this imperative: We have the duty to increase our ecological and technological knowledge, because although technological and industrial progress have led humanity to the edge of a catastrophe, it is only with technology that this catastrophe can be prevented. This duty, however, must not lead to blind trust in technology, but must stand in the awareness that scientific knowledge is necessarily linked to a structural ignorance. This ignorance consists in the fact that science can explain retrospectively what happened, but can never predict with certainty the harmlessness of a new technology. Just think of CFCs: For decades they were produced in large quantities without hesitation until Joe Farman discovered the hole in the ozone layer above Antarctica in 1985 and explained its cause (cf. Farman et.al. 1985.). According to Jonas, we must also not make a bet on the future by recklessly using a technology and trusting that the problems possibly associated with it will somehow be solved by further technologies (cf. Jonas 1979: 76-83.). In the face of new technologies, we should therefore hope less for the possible gains, but rather, in the sense of a "heuristic of fear," keep in mind what risks are associated with them in the worst case; especially since people, quite pragmatically, agree much more easily on what evil is to be avoided than on what gains are worth striving for (cf. Jonas 1979: 63-66.).

In regard to the difficulties of an ethics of the future mentioned above, Jonas' imperative at first seems to be an elegant solution. But a look at the justification reveals serious problems, which put this apparent elegance into a doubtful light: Teleology, metaphysics and a conclusion from is to ought, as it has been known since 1903 as naturalistic fallacy, constitute the core of the justification scheme. The justification of the imperative of future ethics follows approximately the following line of thought:

- Human beings are the only ones in the world who can act responsibly.

- From the capability arises the duty to act responsibly.

- The purpose of humankind is that there is a being in the world that can act responsibly.

- It is something good (has moral value) that there is a being in the world that can act responsibly.

- Thus the duty of man is to maintain the capability (purpose and value) permanently.

The drama of this justification scheme is that one can morally justify all kinds of nonsense with it by following a simple recipe: One writes into what is to be justified a purpose given by nature, in order to finally claim that it should be the way it is, because only in this way it fulfills its natural purpose. Thus it is easy to justify also the opposite of Jonas' imperative; even if it is only to draw attention to the problematic justification: The purpose of nature and evolution is the diversity of the living. Mankind contradicts this purpose by exterminating other species en masse. Thus nature and evolution fulfill their purpose, if mankind disappears as fast as possible from the earth.

Hans Jonas was aware of the problematic nature of his justification, and he meets the undoubtedly expected criticism by questioning, for his part, the rejection of metaphysics and naturalistic fallacies

(cf. Jonas 1979: 92-102.); and in this respect his blatant recourse to justification schemes long thought to be outdated has some originality. And if I interpret Jonas correctly at this point, he is concerned either with accepting the questionable justification scheme or with being without any future ethics, while increasing environmental problems and extreme weather events caused by climate change demonstrate daily how necessary a future ethics is.

2. What (and how much) should be sustained?

The second question focuses on the exact meaning of the term sustainability. Originally, the term comes from forestry. In 1713 Hannß Carl von Carlowitz wrote about a continuously persistent sustainable use

(Carolowitz 1713: 105. Own translation.) of the forest. On the question of what we should understand by sustainability today, I will present the economic philosophical positions of Robert Solow and Herman Daly, both economists of the first rank. They agree that sustainability must be defined neither in a too concrete nor in a too abstract way. Too concretely defined terms, for example in the form of a list of sustainable and unsustainable actions, say nothing about the principle that must underlie this list: Examples do not give a principle. Too abstract and comprehensive terms, on the other hand, are at risk of meaning everything and ultimately nothing; and this is precisely what often happens in definitions of sustainability.

This can be illustrated by the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which cover everything related to sustainable development on the basis of 16 objectives. This makes sense, provided that the transformation of the world is a comprehensive process; but the comprehensive definition also leads to questionable results: The 8th goal is economic growth, and the European Union's web page on the Sustainable Development Goals states that GDP has grown in the EU and that this Sustainable Development Goal has thus been met. But if in the rich countries of the EU the growth of GDP, i.e. usually more production, more consumption and more waste can be considered as a step towards sustainable development, then the concept of sustainability has lost its meaning. Furthermore, this multitude also contains conflicting goals: Poverty alleviation and economic growth conflict with the goal of reducing climate impact by lowering carbon dioxide emissions. The Sustainable Development Goals do not contain a principle to decide such conflicts, and consequently very contrary policies are possible under this definition of sustainability. What is sustainability

supposed to mean, if contrary actions are both considered sustainable?

Robert Solow and Herman Daly agree that a successful definition of the term must meet the proper balance between concreteness and abstraction. And in order to achieve such a definition of the term, both ask the same question: what and how much should actually be sustained? They disagree on how to answer this question.

Robert Solow: Weak Sustainability

Robert Solow's answer to this question is known as the concept of weak sustainability

. According to this, what is to be preserved for future generations is not a particular thing, but the capability to enjoy a standard of living at least as high as our present one:

The duty imposed by sustainability is to bequeath to posterity not any particular thing […] but rather to endow them with whatever it takes to achieve a standard of living at least as good as our own and to look after their next generation similarly.

Solow (1992): An Almost Practical Approach to Sustainability. S. 258.

Solow interprets the standard of living as a kind of return on the capital available in a society. Thereby Solow means capital in the broadest sense

(Solow 1992: 259.). This includes mineral resources, renewable resources, the man-made capital that is usually referred to as capital

, but also education and technology and even nature. In the course of the economic process, this capital degenerates and must be replaced, as is known of man-made capital. This is also true for education and technology. The technology of a typewriter and its repair is no longer needed today. In its place is the technology of the computer, the printer and e-mail. Education, too, must be constantly renewed, because the people in whose education investments have been made will retire at some point.

Thus, in order to maintain the standard of living in the long run, the total capital of society must remain equal, must produce at least a constant rate of return. From this perspective, the economic process can be thought of as a constant transformation of one kind of capital into another. This is particularly illustrative in the case of non-renewable resources: when we extract and use them, that is, when we consume this kind of capital, we must at the same time ensure that this capital is replaced by another kind of capital: We exploit oil to produce gasoline and diesel, and at the same time we construct renewable energies that can be used to power electric cars in the future.

Accordingly, a society must make two decisions in each economic period: How much of the non-renewable resources should be consumed, and how much should be invested for their future replacement? These decisions, Solow argues, can be thought of as an exchange with future generations: By consuming a non-renewable resource, we deprive future generations of the opportunity to use it; and we give a renewable resource in return. If this exchange is fair, then there is intergenerational justice, and this is synonymous with the sustainable maintenance of living standards. This definition of sustainability in terms of these two choices has three main advantages, according to Solow: First, the amount of total capital available is, yet not exact, but in principle measurable; and Solow attaches importance to this: "talk without measurement is cheap" (Solow 1992: 254.). Second, it is clearly determined what is sustainable and what is not. If the total capital is at least maintained, one operates sustainably, and otherwise not. And third, these two decisions are politically implementable in concrete terms, provided that these decisions are based on measurable quantities and not on ideologies.

Solow's explanation of sustainability can also be expressed this way: We must not consume natural capital without replacing it with man-made capital. Solow claims that natural capital and man-made capital are, as economists say, substitutes

. An example illustrates what this means: Cheese rolls can be made with both rye and wheat rolls. They are substitutes. But you always need rolls and cheese, and you can't replace missing cheese with more rolls. Cheese and rolls are therefore not substitutes, but are called complements

by economists. The assumption that natural and man-made capital are substitutes is considered by Solow to be a minimal optimism, without which sustainability is inconceivable, because otherwise one could only ask how quickly or slowly the irreplaceable stock of natural capital should be used up. Solow explains this minimal optimism with the well-known metaphor of a clock:

Without this minimal degree of optimism, the conclusion might be that this economy is like a watch that can be wound only once: it has only a finite number of ticks, after which it stops. In that case there is no point in talking about sustainability, because it is ruled out by assumption; the only choice is between a short happy life and a longer unhappy one.

Solow (1992): An Almost Practical Approach to Sustainability. S. 255.

This assumption will be fundamentally criticized by Herman Daly, and I will turn to it in a moment. Before that, I would like to reflect on Solow's notion of sustainability myself with three critical remarks:

First, Solow argues that the total capital of humanity is sufficiently precise quantifiable by econometric measurement. But how would one quantify the value of nature? How valuable would an industrial use of the Wadden Sea nature reserve have to be for us to be willing to sacrifice the nature reserve for that industry? And how much capital does it take to run a liter of gasoline? Given the enormous complexity of the human economy on the one hand and that of the ecosystem on the other, how would anyone be able to estimate that with sufficient accuracy? Or: In this wager for the survival of future generations, who would bet his own life on having estimated ±30 percent accurately how much capital it costs to burn a liter of gasoline?

Second, regardless of whether a measurement of total capital can succeed with sufficient accuracy, we already face a structural ignorance. The history of environmental problems has shown that we do not know what this total capital actually is: CFCs were long considered completely harmless, and the ozone layer would not have appeared in Solow's account as depleted natural capital at all. For oil, coal, and gas, it was long held that these would eventually be used up; but no one reckoned that the crucial natural capital was the atmosphere's capacity to absorb carbon dioxide. How are we to quantify this total capital when we have already been so mistaken about what that capital is?

Third, Solow's concept of sustainability in principle allows infinite growth. The concept of infinite growth is closely linked to the idea of infinite human needs and the idea of wanting more and more

. If one admits that the environmental problems we want to counteract with sustainable development also have to do with wanting more and more

, then Solow's concept of sustainability, which does not address human greed or other limits to growth, must at least be incomplete.

Herman Daly: Strong Sustainability

Herman Daly contrasts the concept of weak sustainability with that of strong sustainability. The most significant difference to Solow's conception is to see natural capital and man-made capital not as substitutes but as complements.

Man-made capital cannot substitute for natural capital. Once, fish catches were limited by the number of fishing boats (man-made capital) at sea. Few fishing boats were exploiting large populations of fish. Today the limit is the number of fish in the ocean – many fishing boats are competing to catch the few remaining fish. Building more boats will not increase catches. To ensure long-term economic health, nations must sustain the levels of natural capital (such as fish), not just total wealth.

Daly (2005): Economics in a full world. S. 16.

The thought that Daly expresses here in his own very direct and vivid way is the following: The problem of sustainability is that the stress limits of the ecosystem have been reached by the scale of the human economy. Therefore, it falls short to refer sustainability to the standard of living and the substitution of non-renewable natural resources by renewable man-made resources. Economy happens within the ecosystem Earth

and human economy depends on the preservation of this ecosystem: The natural resource ecosystem

is the necessary complement of our whole economy. We cannot do without nature; and therefore sustainability must focus not on replacing nature, but on protecting it.

This comprehensive view on our economic activity in the ecosystem leads directly to limits of growth. Daly determines them in terms of thermodynamics as is common for Ecological Economics: Therefore, our economic activity means that raw materials of low entropy become wastes of high entropy. In order to sustain life and economic activity on Earth in the long term, the wastes must become raw materials again. This requires energy, and this only comes at a constant rate from the sun into the biosphere. Therefore, this energy input imposes physically immovable limits on consumption, thus the economy cannot grow infinitely in a world of finite extent. Or in the words of Herman Daly:

But the facts are plain and uncontestable: the biosphere is finite, nongrowing, closed (except for the constant input of solar energy), and constrained by the laws of thermodynamics. Any subsystem, such as the economy, must at some point cease growing and adapt itself to a dynamic equilibrium, something like a steady state. Birth rates must equal death rates, and production rates of commodities must equal depreciation rates.

Daly (2005): Economics in a full world. S. 13.

To this physical limit of growth, Herman Daly adds a microeconomically based limit that focuses on our well-being. The idea is that every increase in production and consumption is accompanied by two effects. On the one hand, any increase in consumption increases our well-being. On the other hand, every increase in consumption is also associated with more production, work and effort, and accordingly something is subtracted from our well-being. In addition, with each increase in consumption, well-being increases, but less and less; while with each increase, expenses subtract more and more from well-being. It follows that there must be a point beyond which every increase in consumption (and production) subtracts more from well-being than it adds. From this point on, Herman Daly speaks of uneconomic growth

.

Herman Daly contextualizes this critique of limitless growth into the history of economics. There have been three major criticisms of economics: Thomas Malthus criticized it for abstracting from population growth, Karl Marx for abstracting from class struggles and inequality, and John Maynard Keynes for abstracting from uncertainty and the impossibility of full employment. These criticisms, says Daly, have been extensively debated by economists for several generations, yet their answer for all three problems has always been the same: Growth is the solution. The critique of Ecological Economics is that classical economics abstract from social and ecological limits of growth, and therefore growth cannot be the answer to all problems. (Daly 1996: 25f.)

It is thus obvious what sustainability means according to Herman Daly and Ecological Economics. Daly defines sustainability in terms of thermodynamic throughput. According to this definition, an economy is sustainable if it does not consume more raw materials than the ecosystem can regenerate and does not produce more waste than the ecosystem can absorb:

Sustainability can be defined in terms of throughput by determining the environment's capacity for supplying each raw resource and for absorbing the end waste products.

Daly (2005): Economics in a full world. S. 15.

Three precepts follow from this definition:: 1. we must not produce more waste than the ecosystem can absorb. 2. we must use renewable resources only to the extent that they can be renewed. 3. we must use non-renewable resources only to the extent that we create renewable substitutes, as Robert Solow also demands. – If we respect these precepts, our economy is sustainable.

The concepts of weak and strong sustainability differ in four key aspects: 1. Weak sustainability only looks at the system of economy, whereas strong sustainability looks at the whole ecosystem and considers our economy as a subsystem. 2. Limits to growth are not considered in the concept of weak sustainability, while strong sustainability addresses the limits to growth in a finite ecosystem. 3. natural and man-made capital must be seen as substitutes in the sense of minimal optimism within weak sustainability. Strong sustainability conceives nature and technology as complements. 4. Weak sustainability calls for the preservation of the standard of living, while strong sustainability demands the preservation of nature and the ecosystem as the basis of humanity's existence.

John Stuart Mill: The Stationary State

If the talk is of limits of growth, of less consumption or, as in Prof. Paech's lecture, of a post-growth economy, then people often get skeptical. They wonder what this could mean for themselves and fear a poor life that offers little joy. I would like to reply to these fears in a final word with an uplifting thought by John Stuart Mill.

At the outset, a remark on the historical context of this thought: Limits to growth are by no means a modern idea in the history of economics, but can also be found in the economic classics of Adam Smith (Wealth of Nations

of 1776) and Thomas Malthus (The Principle of Population

of 1798). Adam Smith assumed that growth must come to an end because at some point all net investments have been made and the total capital of a society cannot grow any further. But the majority of people are only well off as long as total capital grows and there is a constant shortage of workers. Thomas Robert Malthus believed that population basically grows more than food production could grow, so cyclical hunger crises are the fate of humanity. These pessimistic ideas are contrasted by John Stuart Mill in the Principles of Political Economy

of 1848 with a positive picture of an economy in the stationary state

. The stationary state

means:

a well-paid and affluent body of laborers; no enormous fortunes, except what were earned and accumulated during a single lifetime; but a much larger body of persons than at present, not only exempt from the coarser toils, but with sufficient leisure, both physical and mental, from mechanical details, to cultivate freely the graces of life, and afford examples of them to the classes less favorably circumstanced for their growth. This condition of society, so greatly preferable to the present, is not only perfectly compatible with the stationary state, but, it would seem, more naturally allied with that state than with any other. […]

If the earth must lose that great portion of its pleasantness which it owes to things that the unlimited increase of wealth and population would extirpate from it, for the mere purpose of enabling it to support a larger, but not a better or a happier population, I sincerely hope, for the sake of posterity, that they will be content to be stationary, long before necessity compels them to it.

It is scarcely necessary to remark that a stationary condition of capital and population implies no stationary state of human improvement.

Mill (1848): Principles of Political Economy.

Book IV, Chap. VI. § 2.

Literatur

Carlowitz, Hannß Carl von (1713): Sylvicultura oeconomica –Anweisung zur wilden Baumzucht. Leipzig. Online at Archive.org.

Daly, Herman (1996): The challange of ecological economics: historical context and some specific issues. In: Elgar, Edward (Hrsg.): Ecological economics and sustainable development. Selected essays of Herman Daly. Cheltenham, Northampton. 2007. Pages 25-31. Online at Archive.org.

Daly, Herman (2005): Economics in a full world. In: Elgar, Edward (Hrsg.): Ecological economics and sustainable development. Selected essays of Herman Daly. Cheltenham, Northampton. 2007. Pages 12-24. Online at Archive.org.

Eurostat: Sustainable Development Goals Visualization. Eurostat-Webseite, last visited: 29.03.2023.

Farman, J. C.; Gardiner B. G.; Shanklin, J. D. (1985): Large losses of total ozone in Antarctica reveal seasonal ClOx/NOx interaction. In: Nature. Vol. 315. 16. May. 1985. Pages 207 - 210.

Jonas, Hans (1979): Das Prinzip Verantwortung. Versuch einer Ethik für die technologische Zivilisation. Frankfurt am Main. Online at Archive.org.

Malthus, Thomas (1798): An Essay on the Principle of Population. An Essay on the Principle of Population, as it Affects the Future Improvement of Society with Remarks on the Speculations of Mr. Godwin, M. Condorcet, and Other Writers. Electronic Scholarly Publishing Project 1998.

Mill, John Stuart (1848): Principles of Political Economy. Volume 2. London, New York 1900. Online at Archive.org.

Parfit, Derek Antony (1984): Reasons and Persons. Oxford. Online at Archive.org.

Smith, Adam (1776): An Inquiry Into The Nature And Causes Of The Wealth Of Nations. London. Digitale Ausgabe von MetaLibri. Amsterdam, Lausanne, Melbourne, Milan, New York, São Paulo 2007. Online at Metalibri Digital Library.

Solow, Robert (1992): An Almost Practical Step Towards Sustainability. In: Oates, Wallace E. (Ed.): The RFF Reader in Environmental and Ressource Policy. 2nd Edition. Washington 2006. Pages 253 - 262. Online at Archive.org.

Bernd Neumann,